Votive

Maria Ah Hyun Stracke

July 10 - Aug 23, 2025

Opening Reception: Thursday, July 10 | 6-9 pm

Closing Reception: Thursday, August 14 | 6-9 pm

Open Saturdays from 12-5pm or by appointment

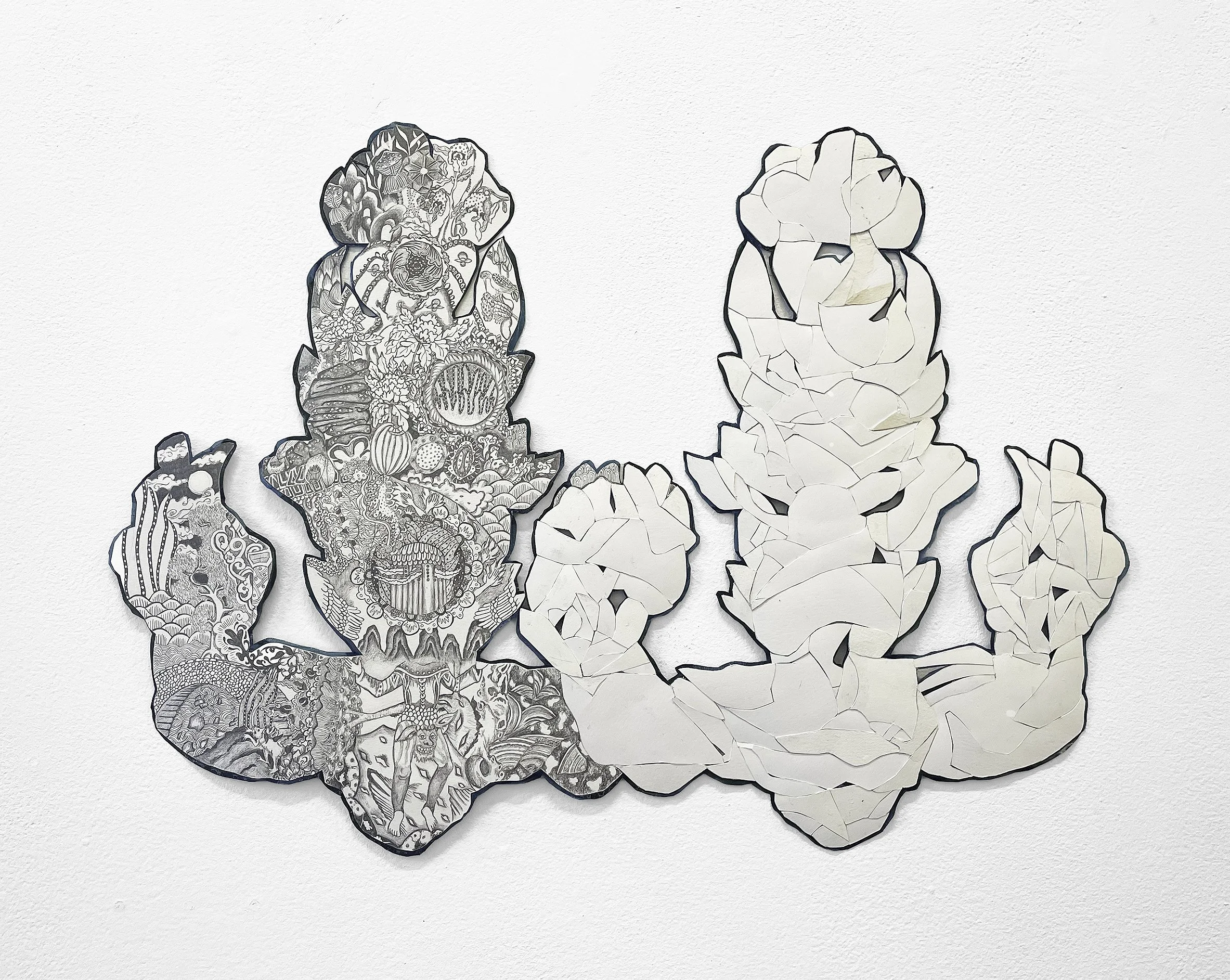

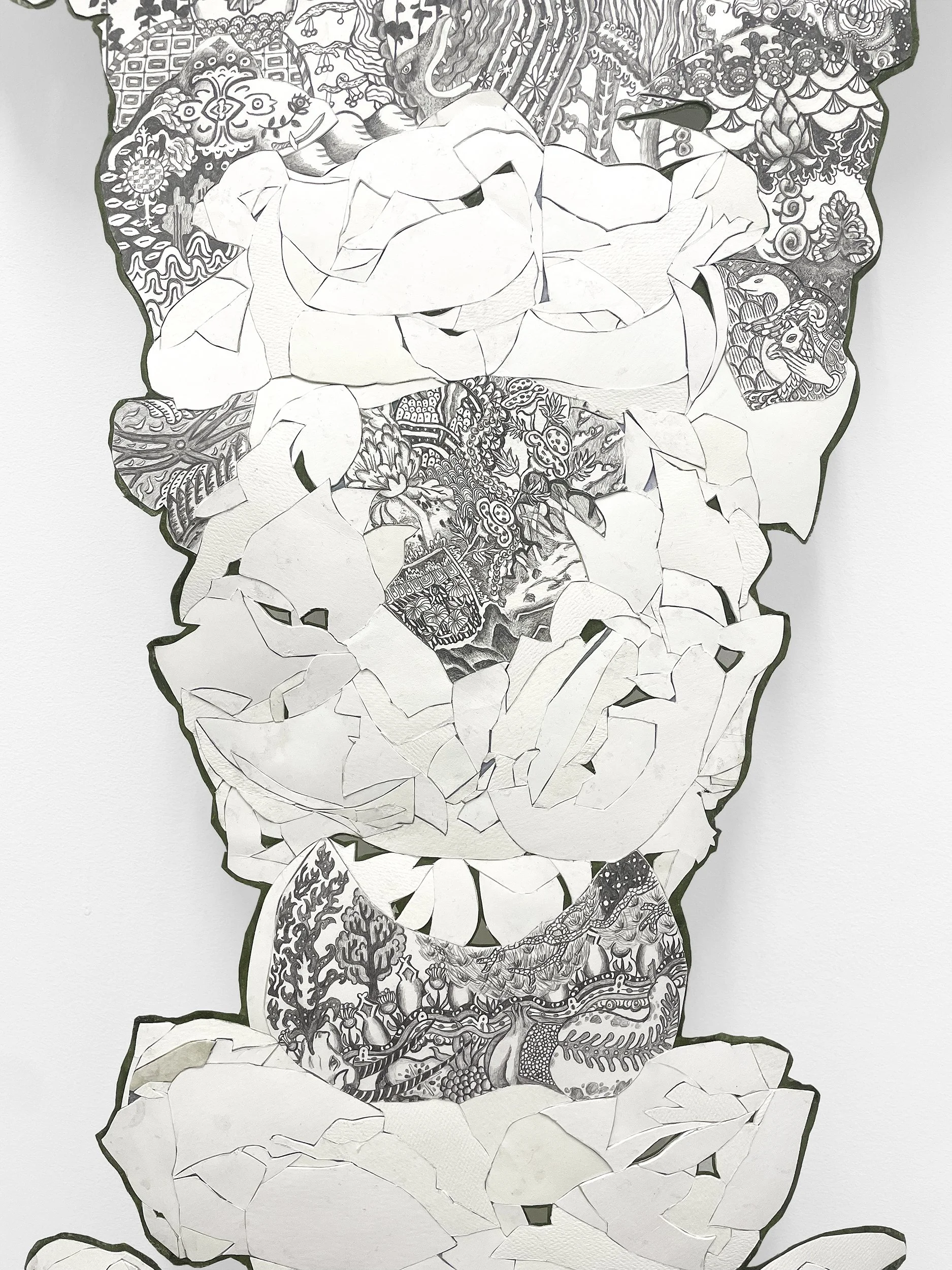

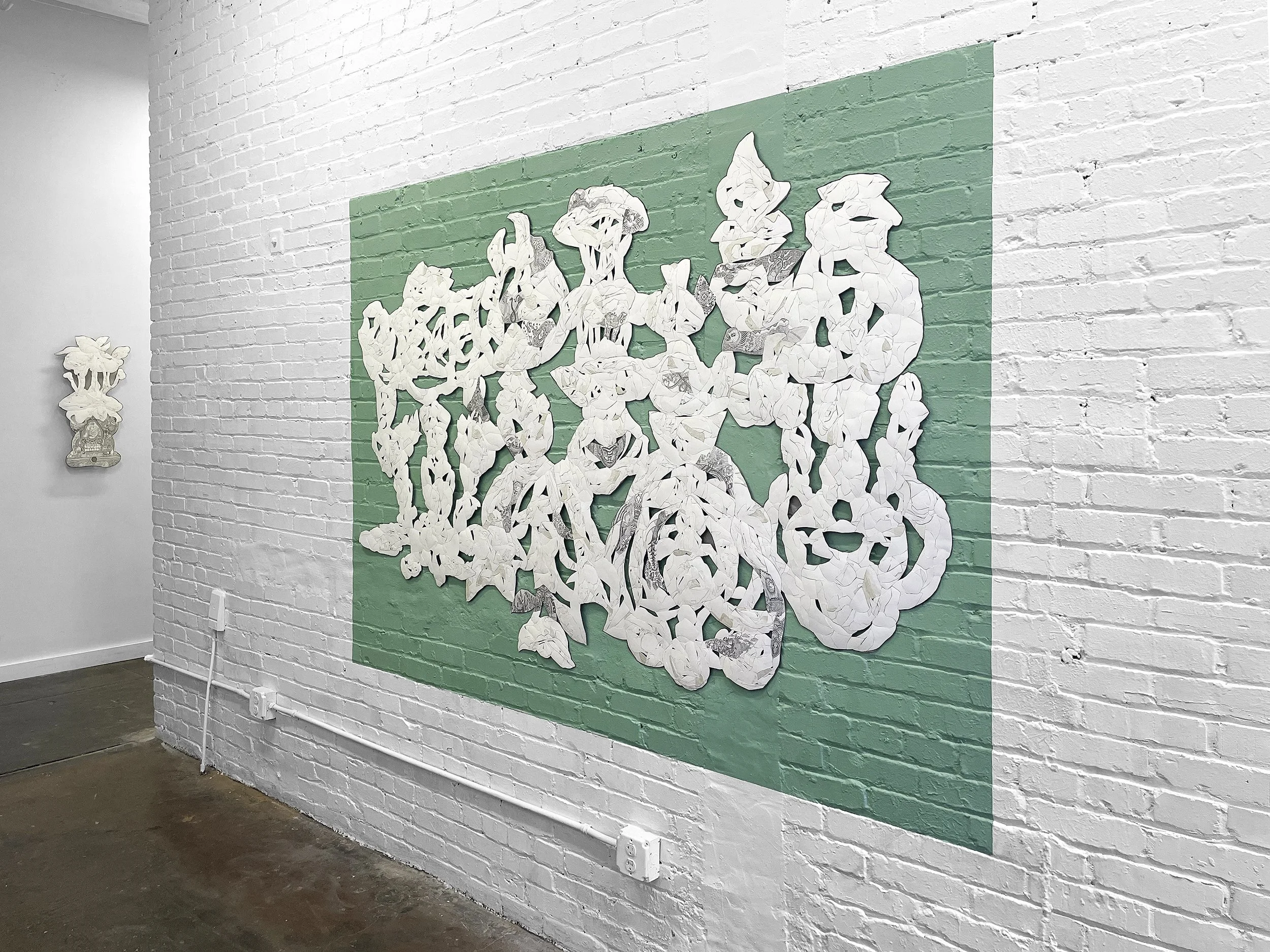

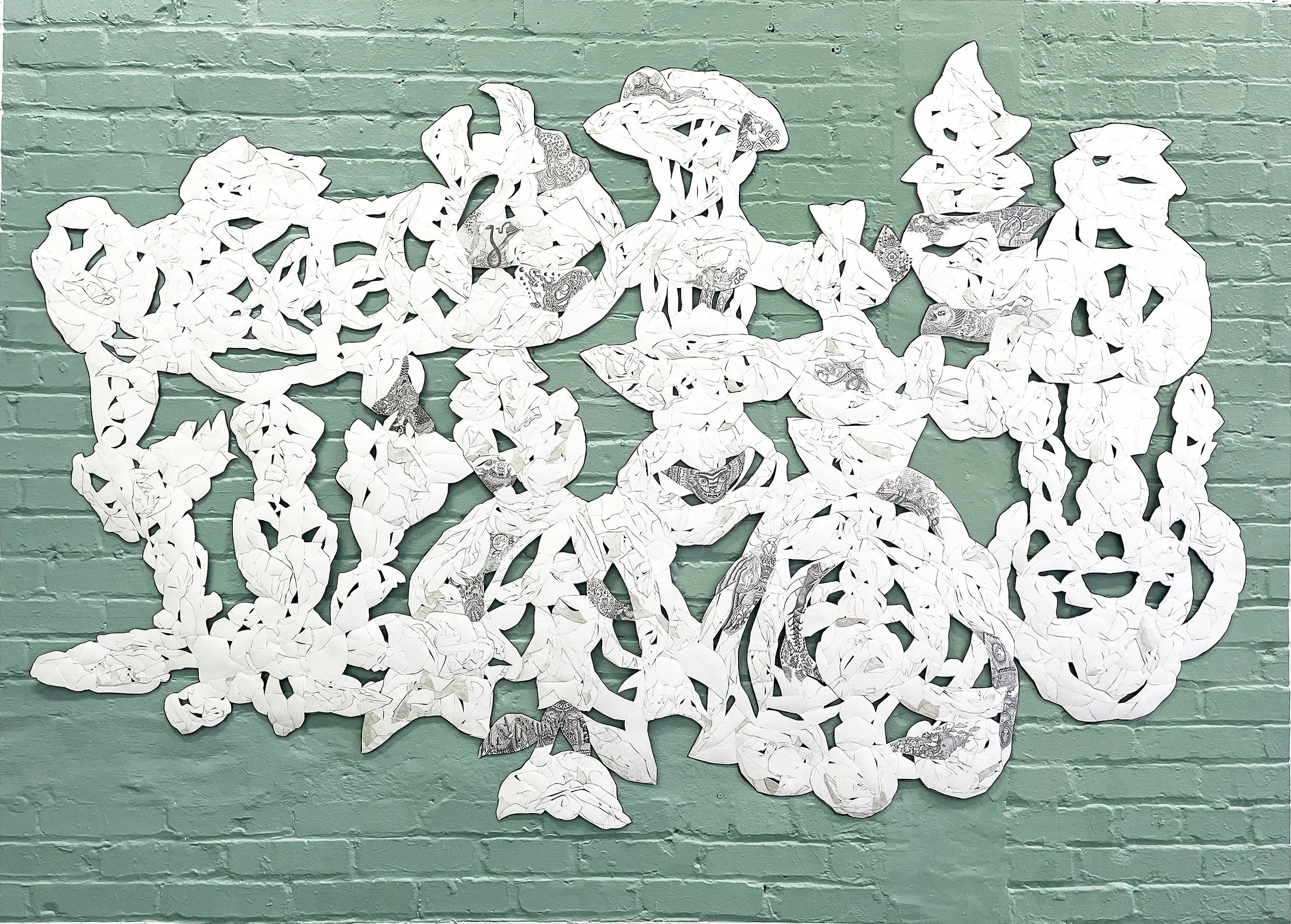

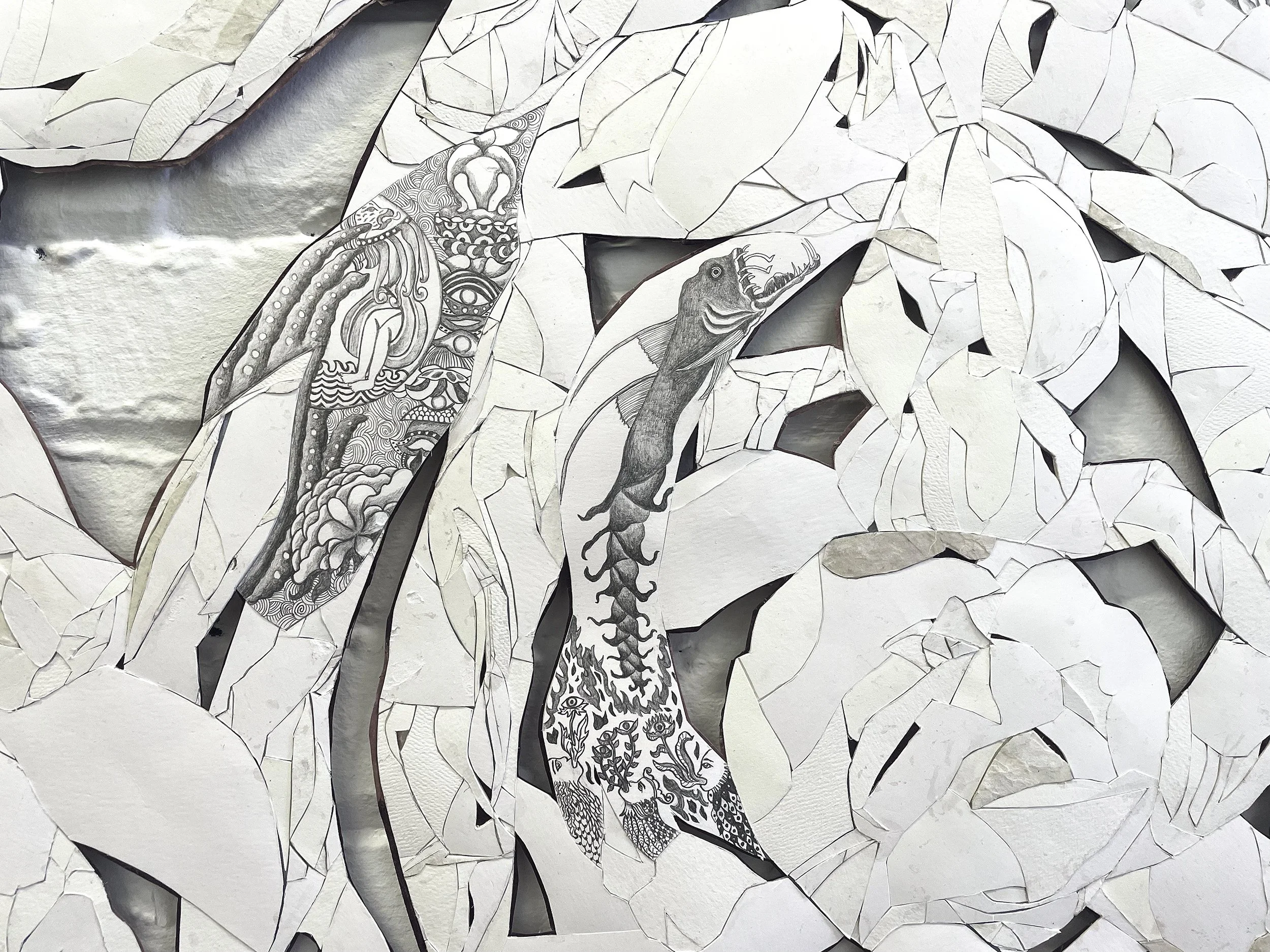

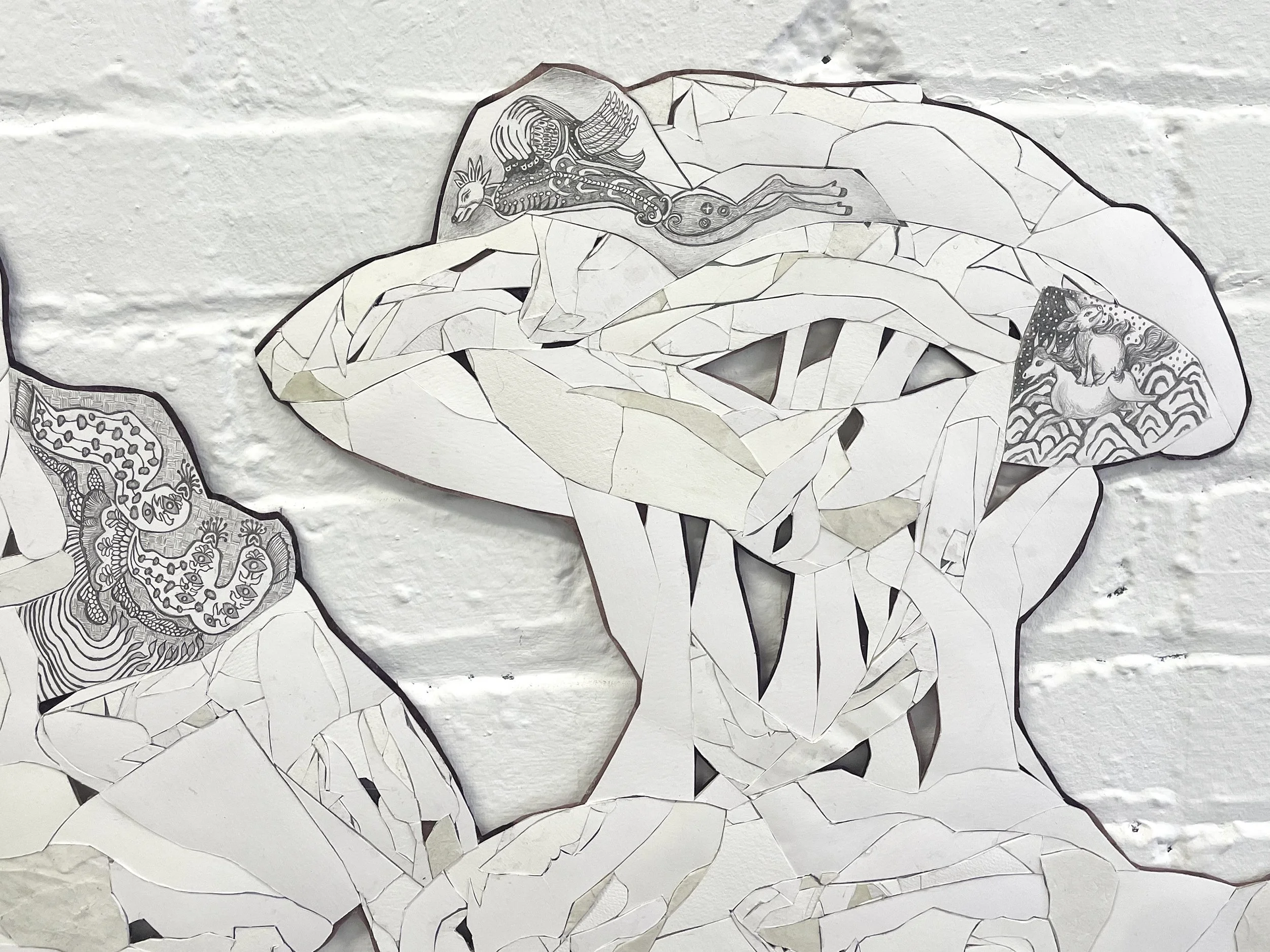

Peep is pleased to present Votive, a solo exhibition featuring new drawings by Maria Ah Hyun Stracke. Moving away from traditional rectangular drawing formats, her precise paper cutting and collaging of hanji (traditional Korean mulberry paper) form layered, permeable surfaces that resemble mountainous terrains, abstract landscapes, and intricate architectural forms.

The drawings' imagery, including figures, patterns, landscapes, symbolic creatures, and plants gleaned from Korean folk and artistic traditions and Western religious mythology and iconography, are rendered in delicate graphite. They explore the concept of a votive: a marker of intimacy between humans and the sacred, often comprising offerings. Votives, typically found at natural sites near homes, serve as both objects and acts of ritual, acting as gateways into sensory experiences and ongoing responses to loss or departure.

In Stracke’s works, there is a strong contrast between detailed graphite drawings and blank, white spaces. This highlights sensory experiences and the feeling of emptiness within the votive. The votive represents a moment frozen in time, sitting between making an offering and having a wish come true. It symbolizes an act made to fill a void, respond to a loss, or satisfy an absence. The act of offering can be very personal and intimate, or sometimes unknown or invisible to others.

Votive is a testament to a fundamental desire to transcend the everyday, generating spiritual resonance through mundane materials and familiar images.

Maria Ah Hyun Stracke is a Philadelphia-based artist and educator who works primarily with hanji (traditional Korean mulberry paper), silk, graphite, paper, and handmade paper clay. As each composition evolves, varied surfaces, shapes, and seams emerge and interact with one another to develop an intuitive material language. Stracke holds a PhD in Literature and Criticism from The Graduate Center - City University of New York and an MFA in Painting and Drawing from Tyler School of Art and Architecture at Temple University.